e-flux Journal #146 // The Hacking of Culture and the Creation of Socio-Technical Debt

Culture is increasingly mediated through algorithms. These algorithms have splintered the organization of culture, a result of states and tech companies vying for influence over mass audiences. One byproduct of this splintering is a shift from imperfect but broad cultural narratives to a proliferation of niche groups, who are defined by ideology or aesthetics instead of nationality or geography. This change reflects a material shift in the relationship between collective identity and power, and illustrates how states no longer have exclusive domain over either. Today, both power and culture are increasingly corporate.

Blending Stewart Brand and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, McKenzie Wark writes in A Hacker Manifesto that “information wants to be free but is everywhere in chains.” Sounding simultaneously harmless and revolutionary, Wark’s assertion as part of her analysis of the role of what she terms “the hacker class” in creating new world orders points to one of the main ideas that became foundational to the reorganization of power in the era of the internet: that “information wants to be free.” This credo, itself a co-option of Brand’s influential original assertion in a conversation with Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak at the 1984 Hackers Conference and later in his 1987 book The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT, became a central ethos for early internet inventors, activists, and entrepreneurs. Ultimately, this notion was foundational in the construction of the era we find ourselves in today: an era in which internet companies dominate public and private life. These companies used the supposed desire of information to be free as a pretext for building platforms that allowed people to connect and share content. Over time, this development helped facilitate the definitive power transfer of our time, from states to corporations.

This power transfer was enabled in part by personal data and its potential power to influence people’s behavior—a critical goal in both politics and business. The pioneers of the digital advertising industry claimed that the more data they had about people, the more they could influence their behavior. In this way, they used data as a proxy for influence, and built the business case for mass digital surveillance. The big idea was that data can accurately model, predict, and influence the behavior of everyone—from consumers to voters to criminals. In reality, the relationship between data and influence is fuzzier, since influence is hard to measure or quantify. But the idea of data as a proxy for influence is appealing precisely because data is quantifiable, whereas influence is vague. The business model of Google Ads, Facebook, Experian, and similar companies works because data is cheap to gather, and the effectiveness of the resulting influence is difficult to measure. The credo was “Build the platform, harvest the data…then profit.” By 2006, a major policy paper could ask, “Is Data the New Oil?”

Continue Reading

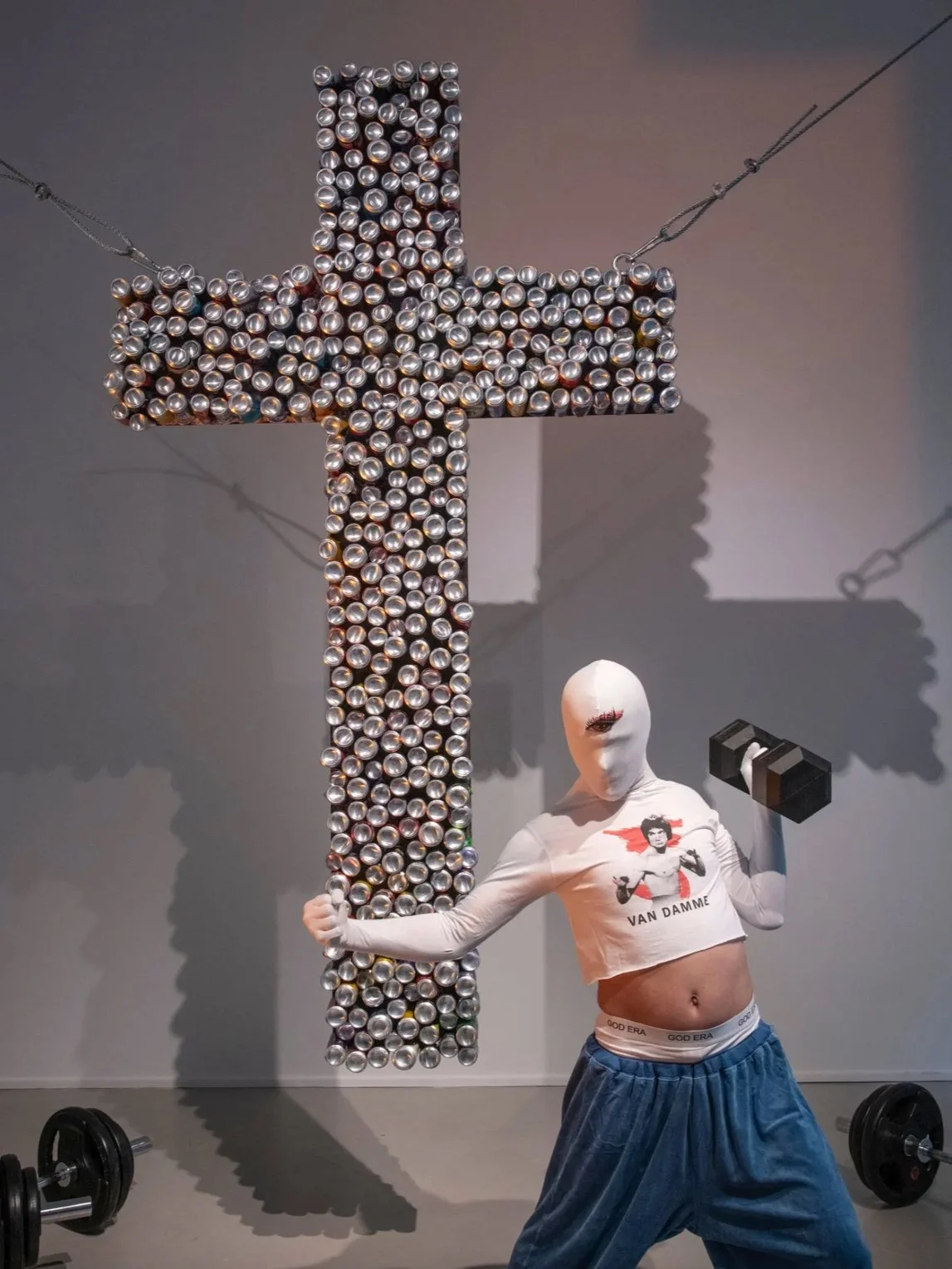

Image credit: John Fullmer, Yzy Gap Psyop Red Round Jacket, 2023. Courtesy of the artist.